The June 18 Letter

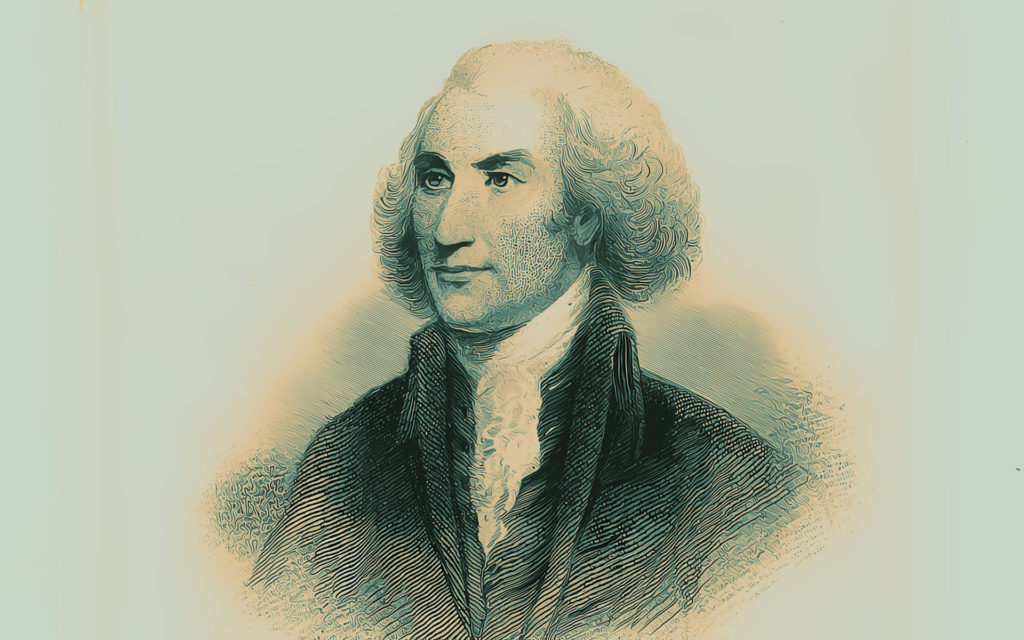

GENERAL PHILIP SCHUYLER

NEW YORK, JUNE 18, 1804 – Somehow a published letter landed on Aaron Burr’s desk

seven weeks after he suffered a 16-point loss in his New York gubernatorial bid. The letter had been published in the Albany Register during the three-day voting period, April 24, 1804 in fact, and was signed by Charles D. Cooper, MD. One sentence of the letter glowed like a live coal to Burr’s eyes:

“I have made it an invariable rule of my life, to be circumspect in relating what I may have heard from others; and in this affair, I feel happy to think, that I have been unusually cautious—for really sir, I could detail to you a still more despicable opinion which General Hamilton has expressed of Mr. Burr.”

Cooper, a political wannebe, was responding to General Philip Schuyler’s letter published days before that his son-in-law was neutral, not working against Burr, and so Cooper’s first letter must be wrong. Schuyler wanted to keep Hamilton’s opposition secret, but Cooper took offense. Was Schuyler calling him a liar?

Burr was still vice president, but he was broke, and his law practice nonexistent. He needed to prove to his own party men, and to the world at large, that he was still a player, and he believed a duel would restore his political credibility, but who could he challenges? And who would accept?

President Thomas Jefferson was a coward and beyond his reach in Washington. Morgan Lewis, who’d just beat him in the gubernatorial election, would surely consider his challenge sour grapes over a lost elections and that he lacked any cause for a duel. Timothy Pickering? That racist senator from Salem, Massachusetts had promised Burr Federalist support if Burr brought New York into his secession plot. Pickering could not or did not rally his troops, but did that give sufficient cause for offense? Who then?

With Cooper’s prickly response to Schuyler, Burr believed he now held the proverbial smoking gun. Hamilton had uttered an unpublished opinion of Burr even “more despicable” than calling him a “dangerous man,” unfit to hold the reins of power.

As he reviewed Cooper’s letter charging Hamilton with uttering a “more despicable opinion” of him, Burr knew it was insufficient to give him cause for a duel challenge, so he worded his letter to Hamilton shrewdly: “You must perceive, sir, the necessity of a prompt and unqualified acknowledgement of denial of the use of any expression that would warrant the assertions of Dr. Cooper.” Burr sent his letter along with the newspaper clipping of Cooper’s letter directing Hamilton to admit or deny he said what Cooper found “more despicable.”

Having just help end Burr’s political career, Hamilton treated this accusation with disdain. He fired back that if Burr informed him what the opinion was, he could admit it or deny it. Unsatisfied, Burr expanded the inquiry and demanded that Hamilton, on his honor, assert he’d never in their long political rivalry spoken of Burr in any way that might be derogatory to his honor. Hamilton could not do that, and so Burr leveled his challenge.

Thirty months before, Hamilton’s eldest son Philip confronted an identical situation. Philip ran afoul of a Burr henchman while he was defending his father’s honor, and the henchman, George Eacker, challenged him to a duel.

Many historians have noted the eerie parallels between the duels of father and son, and label it “coincidental.” Having worked with politicians for most of my professional life, I reject that the son’s duel was merely coincidental. I believe there is a direct causal relationship.

Every time he was challenged before, Hamilton talked his way, so why did he accept now? And why did he violate Rule 13 of code duello and throw away his shot? Hamilton must have seen some benefit to accepting Burr’s challenge, and that benefit, I believe, was expiation, closure and atonement for his son’s death.

Hamilton was not suicidal, nor was he motivated solely in defending his honor. To understand step-by-step what drove Hamilton to accept Burr’s challenge, read my novel Hamilton’s Choice. The father’s death in the most infamous duel in American history was inextricably bound to his son’s death two years before, and I think you will then understand why Hamilton agreed to duel with Burr and thereby widow his wife and orphan his children.