COVID in the time of Hamilton – Part I

PART I – THE DISEASE

As much as the world has, and continues to suffer from the Coronavirus known as COVID-19, we can be thankful that it is not the Black Plague, leprosy or the flu pandemic of World War I. Before widespread sanitation and health care, diseases raged through our cities unchecked. The deadly plague in Alexander Hamilton’s time was yellow fever, a disease that mysteriously killed large percentages of Americans each summer.

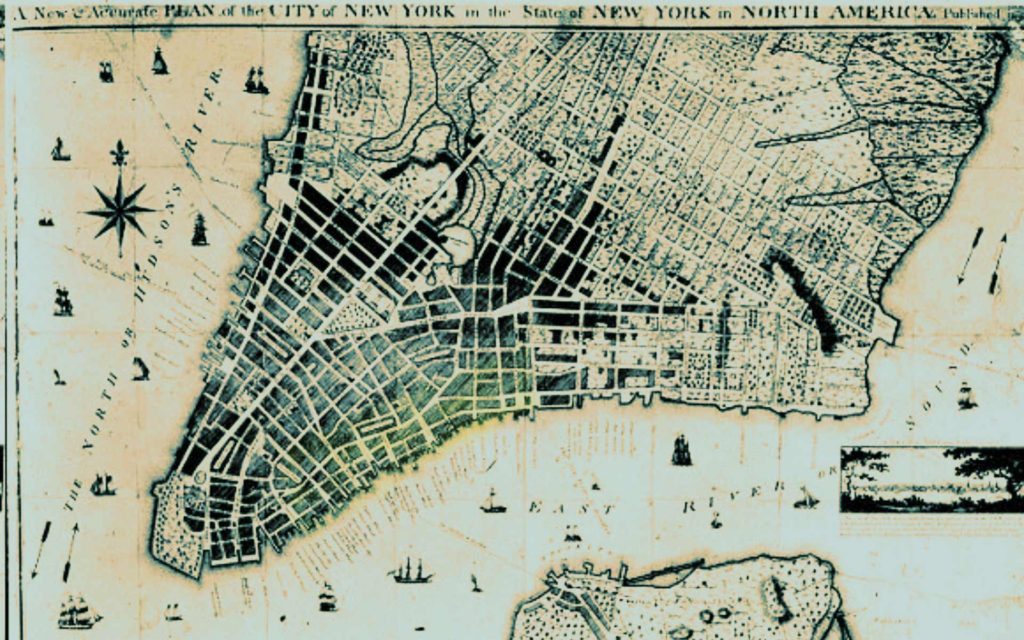

No one then knew that yellow fever was spread the by mosquitos that bred in stagnant, standing water. Back then the city was dotted with ponds and cesspools and privy ditches. Sewage ran into the water supply, polluting wells and town pumps, and the populace generally avoided drinking water in favor of beer and tea and wine. Wealthier folk built homes in the country where they could pass the summer safely until the first frost when it was safe to come home.

Yellow fever first appeared in Philadelphia when refugees from a Caribbean epidemic landed there in 1793. That year, the disease spread through Philadelphia, then the capital of the United States, killing 10% of the population (5,000 in a city of 50,000) by October when the weather turned cold.

Yellow fever began with exhaustion, headaches, and fever, then it yellowed the skin and the eyes and brought mental delirium. Within days victims were vomiting black bile, bleeding from the mouth and rectum, and then they died in agony. Government officials fled into the hills from the plague, but merchants suppressed news coverage, fearing a drop in trade. Rumor carried the news to other places, and it did reach New York.

Upon hearing that the disease ran rampant in Philadelphia, the leading citizens of New York instituted a Board of Health which forbade ships from Philadelphia from landing, and imposed conditions for any ships sailing beyond Bedloe’s Island where the Statute of Liberty now stands. Each ship was inspected and where any hint of the disease was suspected, the ship was turned away. By imposing such travel restrictions, New York escaped the deadly plague, at least for that year, 1793, and the next. But in 1795, as the weather warmed and mosquitoes bred in standing water, New York’s epidemic began. By the end of the summer it had killed thousands of the 60,000 residents.

When Philadelphia was the nation’s capital in 1793-94, Alexander Hamilton lived and worked there as Secretary of the Treasury, but he retired January 31, 1795 and moved back to New York City in time for the outbreak of 1795. Horror stories are recounted from that time, men, women and children dying in the streets, bodies piling up and quickly buried in shallow graves. Some scientific men made a connection between the disease and filthy water. Hamilton’s answer in those years was to send his family north to Albany to stay at his in-laws’ home, and then in 1801 to buy thirty-five acres in northern Manhattan and build his Federalist showplace, the Grange. His attitude toward the deadly disease mirrored his disdain for bullets: he had no fear.

Yes, Hamilton was courageous to the point of recklessness. In August, 1775, for example, the 64-gun British warship Asia occupied New York’s harbor. Hamilton and his brother-in-arms Hercules Mulligan, along with a hundred Sons of Liberty, raided the Battery at the tip of Manhattan one dark night to steal twenty-four cannons. As they hauled the cannon out by ropes, Hamilton handed his musket to Mulligan to hold as he took hold of a rope. By then the warship was in place firing from all of its thirty-two starboard gun ports into the Battery.

When Hamilton asked Mulligan for his musket, the Irishman admitted he had propped the gun against the wall and left it inside when the cannon assault had begun. Hamilton coolly walked back into the Battery in the midst of heavy shelling, nonchalantly returned with his musket and helped haul the cannon away. The raid captured twenty-one of the fort’s twenty-four guns to use for the American cause.

Hamilton’s disdain for risk was a hallmark of his character. When he was finally given a field command at the battle of Yorktown, Hamilton drilled his men just out of range from the British guns so they’d waste their shot. At the command to attack, Hamilton was the first one over the barrier, brandishing his sword, leading his men into the redcoats’ live fire. He was never shy about confronting other attorneys in courtrooms or political opponents in the world of public opinion. Although he came from nothing, this poor orphan from the Caribbean tackled any challenge, persuaded many savvy politicians to vote his way, served as George Washington’s alter ego, and so impressed General Philip Schuyler that he accepted him as a son-in-law.

Hamilton’s courage often bordered on rashness. When his family sheltered in the country during the height of the yellow fever epidemics, he stayed behind in Philadelphia and then in New York in order to work. Unfortunately, this disregard for his own safety and his belief that he could take risks without consequences led him to accept Burr’s challenge, and finally cost him his life.

It was July in Manhattan, a humid, sweltering time that bred mosquitoes, but the battle between the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans grew vicious. He met the conflict with his usual devil-may-care attitude, until his luck ran out.